It is of no surprise to anyone in our community that gun violence has marred this academic year at the University of Virginia. Beyond the horrific and targeted shooting in November,[1] there has been a marked rise in gun violence in 2023. In just the first few months of this year, there have been five homicides in Charlottesville. To put that into perspective, there were zero homicides as recently as 2021.[2] The Chief of Police at UVA, Timothy Longo, said that he had never seen so many killings in a calendar year, let alone in the first three months of one. Before heading the University’s police department, Longo had served as Chief of Police for the City of Charlottesville for nearly sixteen years. To better understand this issue, we sat down with Chief Longo and delved into some of the faculty research on gun violence.

The most recent homicide, which occurred on the Corner while students were celebrating St. Patrick’s Day,[3] is indicative of the type of crime that Chief Longo is seeing in the community. The two suspects knew one another, but “the underlying reasons don’t have much rhyme or reason.” It seems that these are incidents of personal squabbles resolved by shooting. This is a departure from what Chief Longo has historically seen, in which “almost all of [Charlottesville’s] homicides that were not domestic-related . . . were attached to some underlying criminal conduct.” And that conduct was either drug-related or stemming from organized criminal gangs. But Chief Longo did also note that he was unaware of the existence of gangs on Grounds. When asked, Chief Longo opined that the rise in violence experienced by Charlottesville is consistent with national trends.

Before getting into the initiatives that Chief Longo has proposed and their respective merits, it is necessary to understand the role of the University’s police department. Chief Longo explained that the UVAPD operates under a concurrent jurisdiction agreement with the city, granting its officers authority to enforce the laws of the Commonwealth in and around the community. This legal document, which is “much like a contract,” has covered a large parcel of real estate around the University since 2005. And it does serve as a limit beyond which the University cannot address criminal activity. Even small distances can make for litigation on this issue, as was the case in Boatwright v. Commonwealth.[4]

To address the growing risk of gun violence, the University police have increased their supplemental presence in hotspot areas. Thursday through Saturday, University police officers are on special assignment around the Corner from 7 p.m. to 3 a.m. These officers are a part of the Community-Oriented Squad, which will be expanded. Chief Longo is also looking to expand the Ambassador program, which is contracted to a third party, who sends trained responders. They can be identified by their yellow jackets, but are not armed. Their primary duty is to be a “force multiplier” for the UVAPD, reporting back suspicious activity. Their area of coverage has grown since the November shooting, now including the Downtown Mall. Chief Longo also addressed the security system implemented by the University, which maintains over 2,000 cameras on and around Grounds that are linked to a central location. “Everything that we build now has security requirements,” so that particular areas can be immediately locked down remotely.

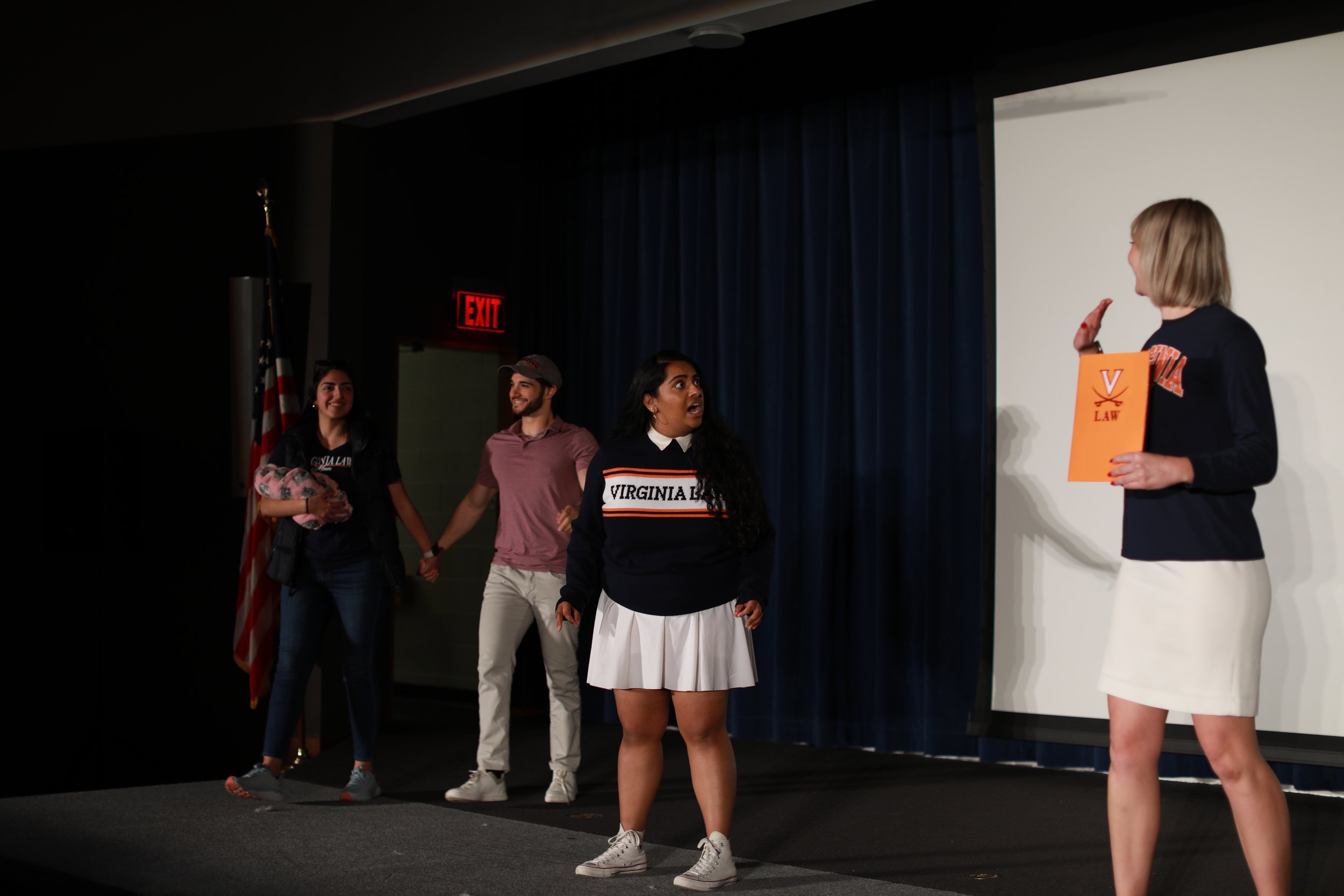

In a town hall addressing the issue of gun violence,[5] President Jim Ryan ’92 addressed the University’s support for a proposed law that would make “carrying a firearm on school grounds a Class 1 misdemeanor and allow law enforcement to obtain a search warrant when it believes firearms are possessed illegally in university buildings.”[6] As of now, the possession of firearms is prohibited in all public buildings owned by the Commonwealth except for University buildings. President Ryan said that the loophole “limits our law enforcement capability.” This is true even though there are administrative prohibitions against possessing a firearm on school grounds, since, as Chief Longo explained, “typically, police departments don’t engage in the enforcement of administrative rules.” Rather obviously, it is problematic to put the burden on untrained University officials when there may be weapons involved. The bill, sponsored by Virginia State Senator Creigh Deeds and Delegate Sally Hudson, failed in the House of Delegates this past term. President Ryan said that the University will continue to push for its adoption.

Chief Longo did offer resources for students concerned about the growing danger in our communities. First, he strongly recommended that everyone watch the Active Attacker Training and Response Video, which outlines how to react when there is an active shooter on Grounds.[7] Second, to help the University’s security system operate effectively, students should honor the access control points (i.e., don’t let people standing by locked doors into the building). And finally, Chief Longo repeatedly stressed the need to plan ahead, considering what you would do were a violent incident to break out. He concluded by advising, “Let’s not make it comfortable for people to victimize us.”

But all of this must leave the general reader somewhat unsatisfied. I appreciate that the University is covered in cameras and armed with a centralized security system, that ambassadors and police officers roam our community, and that people like Chief Longo and President Ryan are at the helm. But that does not change the disquieting nature of the map featured above this article, which shows reported incidents of shots fired, shootings, and armed robberies. Or the fact that the discussion before my Property class was about who was still at the bar when the shooting started. I do not know the answer to this, nor do I pretend like our local officials can serve as ballasts when faced with regional and national crime trends. University police cannot be blamed every time a pistol is stolen near Richmond and finds its way to Charlottesville. But I think I speak for the community when I say that something more needs to be done.

Issues of gun violence and regulation have an obvious connection to the legal field, with various avenues and angles for considering the question. Accordingly, members of the Law School community have turned their eye to the issue of gun violence in their scholarship.

One faculty-member who has focused on the policy side is Professor Richard Bonnie ’69, who has advocated for policies which reach “common ground” in a highly polarizing area.[8] One such area in which Professor Bonnie has been at the forefront is in advocating for red-flag laws. Such laws enable the use of “extreme risk protection orders” (ERPOs), wherein a court (at the request of friends or family) removes firearms temporarily from those concerned to present a risk of harm to themselves or others. A hearing is then held, and if found to present a substantial risk, the weapons are removed for a certain period of time. Nineteen states (and the District of Columbia) currently have versions of such laws on the books, including Virginia.[9]However, while these laws may allow for early intervention, preventing violence against the public or an individual, they rely on those near the at-risk person to report worrying behavior—something people are often reluctant to do. Even when people have concerns, there is a “general disinclination that many of us usually have about interfering in other people’s lives.”[10] In order to be effective, the public must know about the process and be willing to intervene. Accordingly, states enacting such laws need to engage in public education campaigns to inform citizens how and why they should use such laws.

Professor Bonnie has also highlighted the minimum age requirements for obtaining firearms as an area for change. Though not necessarily advocating for a one-size-fits-all approach, Bonnie believes the Second Amendment should not be interpreted as barring the increase of age limits beyond eighteen to twenty-one years old. Instead, Congress and state legislatures should be allowed to grapple with the question “based on a balancing of the liberty of maturing adolescents and the risks of possessing firearms to their own safety and the safety of others.” Emphasizing the cognitive, emotional, and societal development people are still undergoing after the age of eighteen, Bonnie drew parallels to the reduction of motor vehicle crashes which followed raising the minimum drinking age. Even choosing to forego a blanket age restriction, an individualized inquiry assessing the maturity or stability of a youth seeking access to weapons may serve to prevent those likely to cause harm from accessing weapons in the first place, lowering rates of gun violence.

Beyond questions of what policies to enact, one must consider who gets to decide what regulations are in place. This issue of the appropriate level of lawmaking for gun policy brings state and local governments into direct conflict, as differing or adverse policy goals and approaches might be implemented or desired. Professor Richard Schragger, having written extensively on the conflict between city and state governments, highlighted the proliferation of state preemption of local firearm regulations. Such statutes are an attempt by state legislatures to prevent city governments from enacting ordinances or rules counter to their preferences, limiting the power of local officials and (in many instances) opening them up to civil liability.

With regard to firearm preemption statutes, which have proliferated throughout a majority of states, efforts have been “particularly successful in large part because the National Rifle Association has acted aggressively at the state level.”[11] Virginia is one such state which prohibits localities from adopting or enforcing any ordinances or actions regulating firearms, except as expressly authorized by statute.[12] This is reinforced by the nature of Virginia as a Dillon’s Rule state, as opposed to the more common home rule system—another aspect of the state-local relationship which Professor Schragger has advocated to change, both in Virginia and beyond.[13] Under Dillon’s Rule regimes, local municipalities can only exercise those powers expressly granted or delegated by the state government—a further limitation on the ability of urban areas to enact policy at odds with the statehouse. Given that the majority of cities are more liberal than their state governments, especially in states wherein Republicans have a majority or supermajority, such preemption laws prevent cities from enacting policies to address gun violence. Add to this the issue of gerrymandering, including the Supreme Court’s recent endorsement of partisan gerrymandering in Rucho v. Common Cause, and the struggle between cities and states for regulatory control only grows.

These research efforts represent only a portion of the interesting and varied work being undertaken by faculty at the University to address the issue of gun violence. As this problem continues to be felt by communities and areas throughout the nation, such scholarship will enable not only the legal and political spheres to better understand the situation, but the public as well. Such informed scholarship and debate represent an important step in actually dealing with the issue.

---

jxu6ad@virginia.edu

guj9fc@virginia.edu